Louise from A to Z: M for Mr. Pabst, Mr. Flowers, Miss Ruth, Barbara Maybury, George Preston Marshall, Helen Morgan and James Mulcahy

G.W. Pabst, on set

Mr. Pabst was how Louise referred to director GW Pabst, who was possibly the single most important figure in her career and maybe even in her life. Brooks said that the two of them understood each other through a kind of wordless communication, and said that when she met him on the platform for the first time in Germany it was "as if we'd known each other forever." The two of them had a complicated relationship that caused Louise to respect Pabst in a way that she respected few people. As she said in Lulu in Berlin, she wouldn't go back to Hollywood, "but I would go to Mr. Pabst." This is another instance in which the best way to gain insight into their relationship is to read Louise's own piece in Lulu in Hollywood and also to read these hysterical and touching words that she wrote about working with him. Mr. Pabst got some real art out of Louise Brooks, as well as some real thoughts and definitely some great prose later on; simply because he believed in her.

Louise Brooks, age 5, on her porch on Main Street in Cherryvale, KS

Mr. Flowers, sometimes referred to as Mr. Feathers, was another man who had influence over Louise's life, but not at all in a similar or good way. She knew him when she was just a little girl in Cherryvale. He used to dote on her and buy her gifts until he gained enough of her trust to get her alone, at which point he molested her. Louise would recall his effects later in life to Kenneth Tynan: "I was done in by a middle aged man when I was 9," she would say of the awful incident, "[He] must have had a great deal to do with forming my attitude toward sexual pleasure. For me, nice, soft, easy men were never enough - there had to be an element of domination - and I'm sure that's all tied up with Mr. Feathers." (Paris, 548) While the fact that little Louise was taken advantage of was bad enough, what made it worse was that, when she told her mother, Myra blamed her for having led the man on. She would also refer to his effect over her life by saying, "I was loused up by my Lolita experiences." For further reading on this part of Louise's life, consult both Louise Brooks by Barry Paris and Dear Stinkpot by Jan Wahl.

Ruth St. Denis, circa 1922

Miss Ruth was the way that Louise and others in Denishawn referred to Ruth St. Denis, who ran the program with Ted Shawn, or Papa Shawn. Miss Ruth would be the one to dismiss Louise from the dance company after having had a tempestuous yet caring relationship with her. The humiliation that was suffered at the hands of Miss Ruth would stay with Louise long after the incident, but also change her life forever.

Barbara Maybury Andrews is a lovely woman and used to be one of the devoted caretakers of elderly Louise Brooks. She spoke to us in an interview (my first) a year ago and gave us insight into Louise's paranoia, saying that if she went away at any point Louise would leave over a dozen messages on her phone, but she would try not to tell her if she was leaving because Louise would spin out over it with anxiety. She also told us that Louise used to pretend to go hoarse on the phone and claim it was her emphysema when she really just wanted someone to feel sorry for her or to hang up. Barbara also said that Louise was sweet, which was, at the time, the first time I had heard that from anyone.

With the very kind and funny Barbara Maybury Andrews in Rochester, NY

George Marshall, looking dapper as ever

George Preston Marshall could feasibly be seen as Louise's longest running relationship with a man, and he got a lot of praise from her in her later life. She described him as "a tall, black-haired man of twenty-eight with a handsome face that was already marked by a subtle play of cruelty." As for their meeting in 1925, it didn't go so smoothly. "After a party at the Shoreham hotel, he took me, somewhat drunk, to my room at the Willard Hotel. We had been there only a few minutes when there was a knock at the door. George ran into the bathroom and hid behind the shower curtain, while I opened the door to the house detective. He went directly to the bathroom and came out with George. They chatted pleasantly, leaving the room together after accepting a $20 dollar bill from George..." (Paris, 81). This incident would separate them until the Autumn of 1927, when Louise would stumble upon him at a bar and he would buy her a drink; she later referred to this as the most fateful experience of her life. Louise called him "wet wash" because he inherited and owned a laundry company (he would later found the Redskins Football Team), and he called her "Scrubbie," she said, because he had "cleaned her up." (Paris, 198) She would leave Eddie Sutherland to be with Marshall, who would advise her to quit her Paramount contract and go to Berlin so that he could take a European vacation, causing her to make Pandora's Box (1929). He would encourage her to continue her carrier in Hollywood and she would reject the idea, causing him to knock her into a nightstand and leave a permanent scar atop her forehead. He would keep her for years in New York, as can be attested to by one of his old friends who I spoke to months ago, who recalls him doing his budget and putting aside money for "his girlfriend in New York." He would leave Louise officially at some point in the 1930s, later marrying Corinne Griffith. Louise described his mind as having been "panoramic," saying that he had a thousand ideas a day, two of the workable. Louise would even admit later to having been crazy about him and, coming from her, this means quite a lot. She would call his home when they were both old and gray to speak to him, refusing to believe that he was senile after having suffered some health issues. The image is heartbreaking. They were two brilliant and brazen people who functioned very passionately together for a good amount of time. To hear more about George Marshall, watch Lulu in Berlin, in which Louise speaks of him in detail.

Helen Morgan was singing in the bar when Louise met George Marshall again that fateful night, and she lists her as her favorite female singer in her journal.

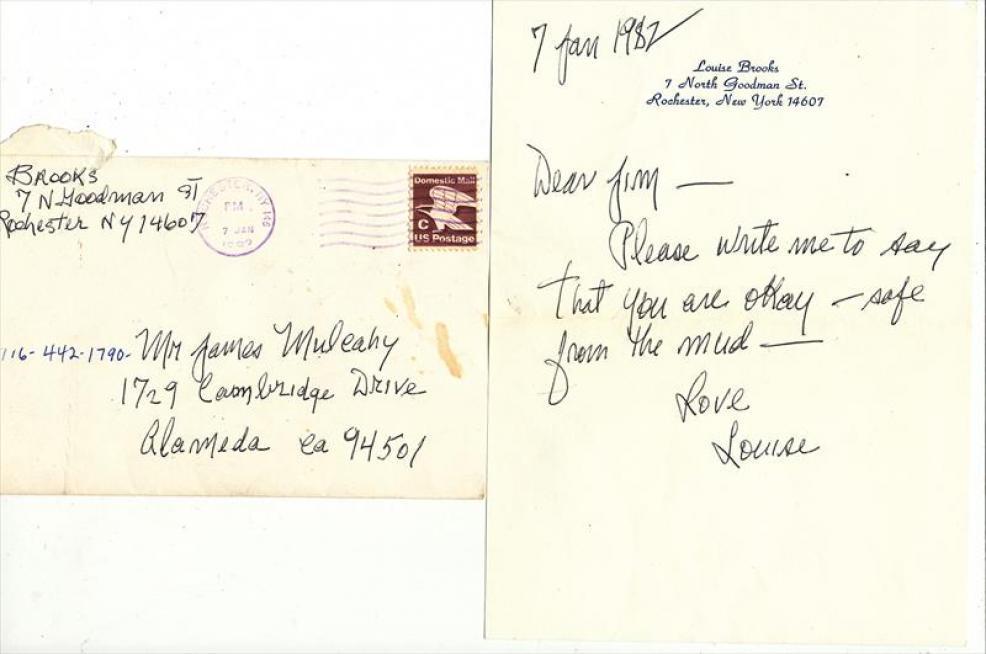

James Mulcahy is somewhat of a hidden figure in Louise's life, but she was supposedly engaged to him at some point in May 1927, or so said Walter Winchell's column. There was little else heard of the proposed union and the marriage never took place. However, letters found after Louise's death that suggest her having written to him well into her later years, always inquiring as to whether he was "safe from the mud."

Letter from Louise Brooks to James Mulcahy, courtesy of Louisebrooks.com